Developmental Sequelae of PTSD in Children

Developmental Sequelae of PTSD in Children

Abstract

Any average, reasonable adult will be able to cite some negative effects that interpersonal trauma may have on a child, but few (even professionals working in the mental health field serving children) are able to cite specific developmental impacts of interpersonal trauma that impair such children. The value of such knowledge to caregivers of children is that it can focus treatment modalities and interventions in such a way as to avoid multiple errors in both diagnosis and the pursuit of inherently ineffective or useless intervention techniques. This article attempts to give an overview of the effects of interpersonal trauma on a child’s development, and how the socio-biological mechanisms of PTSD negatively impact the child’s developmental process.

Interpersonal violence in the form of neglect, physical, and sexual abuse towards children by adults has a wide variety of impacts, from the devastation of the child to the social and economic costs of caring for damaged children. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has determined that nearly one million children are victims of abuse or neglect each year in the United States, with more than 80% of the perpetrators being a parent, and 58% of these being the child’s mother. (May, 2005) While it is clear that children who are victims of interpersonal violence will need some level of services to recover from their potentially life changing experiences of violence from their caregivers, it is not as nearly clear as to what the after effects of such abuse will be for any one such child. In addition, there logically needs to be specific clinical interventions applied in order to mitigate the effects of interpersonal trauma that have been based on an accurate diagnosis of Acute or Post Traumatic Stress in the child. A relatively new area of study, developmental traumatology research, is a system wide, detailed examination of psychological and psychobiological impacts of interpersonal violence on children that can shed light on how abuse results in trauma symptoms, and possible treatment directions for mitigation of the disorder. (DeBellis, 1999).

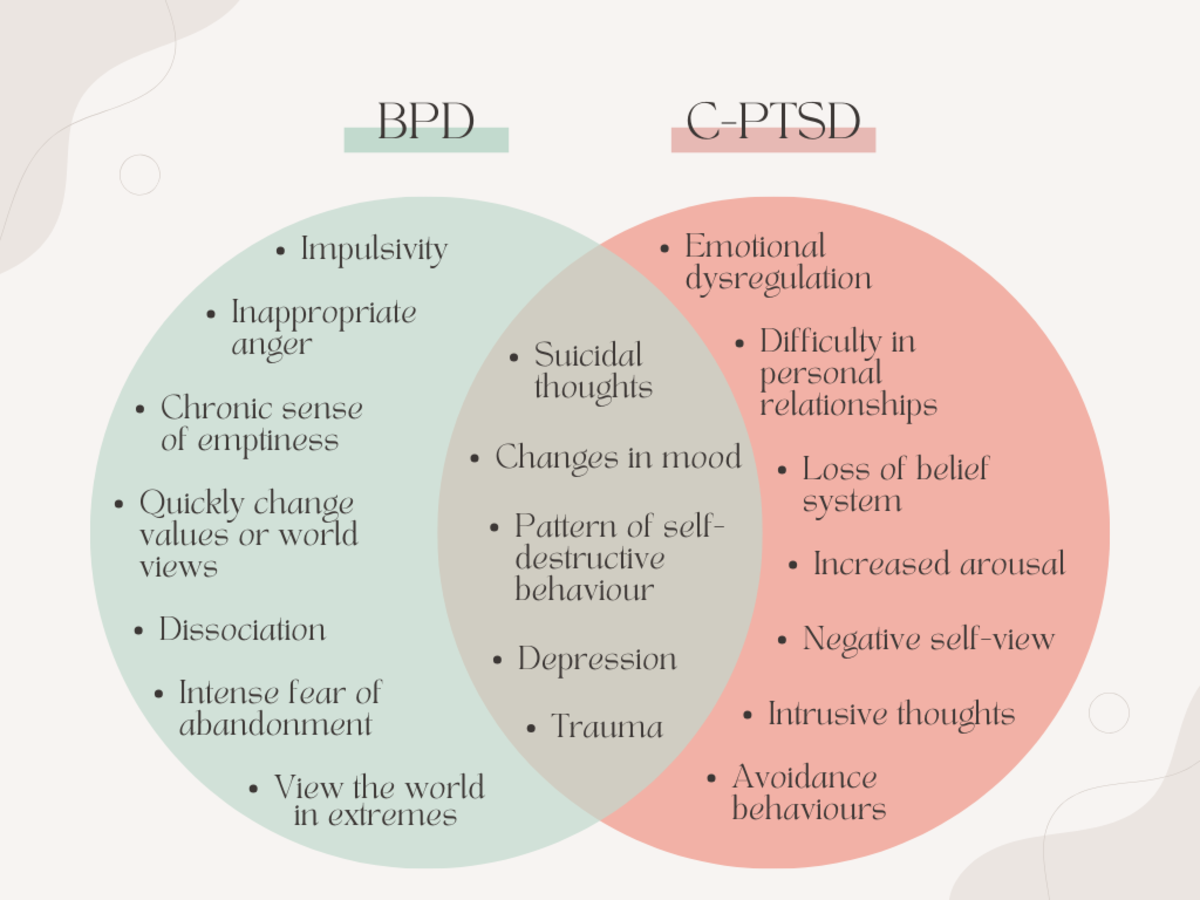

Proper and timely diagnosis is the first challenge, as there is a well-known effect in the diagnostic field that often misdiagnoses stress disorders in children as other mental health diagnoses. (Briere, Elliott, 1997) The danger, of course, of such misdiagnoses is that the child will not receive the correct interventions, and the interventions that are ultimately used will be at least ineffective, if not harmful. In addition, valuable treatment time will be wasted in the process. This is not to say that there cannot be co-morbidity in PTSD cases; in a study by Ford, Racusin, Ellis, Daviss, Reiser, Fleischer, and Thomas, there was found to be a strong correlation between PTSD, ADHD, and ODD. (Ford, et. al. 2000) One may argue in cases that have multiple Axis One diagnoses, which of the maladies should be considered primary, and research regarding “which comes first?” may be quite pertinent to the conversation. In the front-line field of treatment, it is often the case that the initial diagnosis is either ADHD or ODD when in fact, there is a well known and documented history of neglect, abuse, or sexual abuse on file with the local child protection agency.

Childhood might be considered a period of time that is characterized by multiple and overlapping “critical periods” in the course of normative development. (Borderick and Blewitt, p. 23) Traumatic damage through interpersonal violence (here also indicating neglect as a substantially violent act) has the potential to negatively impact one or more of these critical periods. Since effective learning of new developmental skills would logically be seen as a function of these being available to the child (Broderick and Blewitt, p23.), so too would remedial measures designed to mitigate the effects of the violence on the child’s development. Left un-addressed, impairments resulting from the trauma do not simply disappear over some length of time, as many naïve people (and perhaps even some clinicians) would like to believe. Osofsky (2004) cites that even children who are exposed to disruptive care giving (presumably as opposed to physical or sexual abuse) may develop significant problems in emotional regulation, establishing normative attachment, and deficits in social and cognitive processing. (p.54) Perry (1994) asserts that there are developmental periods that provide increased vulnerability to critical incidents, citing the development of the complex chemical stress mediating process, and that once these are altered in utero, infancy, or childhood, they affect the functional capabilities of stress regulation in adulthood.

It stands to reason, then, that when an interpersonal trauma results in a valid diagnosis of Acute or Post Traumatic Stress for a child, the symptoms experienced by the child have the potential to impact any and all developmental areas, especially those that happen to be in a ‘critical period’ of development. It would also stand to reason that as such, each individual child will have a rather unique profile of presentations and effects in their various developmental areas; meaning that PTSD expression in children may be highly variable. Nader (2001) states:

Because of the trauma-induced regressions or precocious development and the interaction of age and other factors (e.g., culture, child traits, previous experience, and/or aspects of the trauma, the effects of age on traumatic experience and response (and vice versa) are complex. Moreover, the competence achieved in one phase affects each subsequent phase. (p.280)

Nader’s contention, then, would indicate that damages and incomplete or impaired achievement of competence in one developmental area or stage might certainly negatively multiple other areas or stages. That there is a symbiotic relationship between developmental areas should not surprise any professional who works with children, but the extent of the ‘domino’ effect may not be as nearly evident or salient to the professional in direct observation of the child. The naïve school teacher or counselor, or event the clinician working slightly out of their field of expertise may sum up the symptoms that they are observing in the child as simply needing a well designed behavior plan. This, of course, only begins to address the complexity of the child’s functioning issues. Genuine treatment efforts need to become aware of the underlying biological sources for the observed difficult behaviors in order to begin to adequately treat the child. Osofsky (2004) theorizes two mechanisms that traumas in early life may make children vulnerable to further negative effects: one is the ability of the child to maintain a neurophysiological homeostasis, and the other related to intersubjective information. (p96). Essentially, Osofsky is referring to the age old argument of ‘nature vs. nurture’: the biological mechanisms that provide the physiological ability for the child to return to calm following stress suffer insults that once damaged, are not prone to self-remediation, and the resulting dysfunction in the child’s human-to-human capacity for accurate, effective, and satisfying exchange caused by the trauma experience. This would be especially complex and salient in situations where a child is living in an abusive and trauma producing situation with a primary care giver that is a perpetrator. Such situations, not being uncommon, become quite pertinent to the earlier reference to adults outside the child’s home experience of the child.

How a particular child responds to a particular trauma event, is dependent on a variety of facets related to development, including the child’s overall developmental level, their attachment relationships, their prior traumatic exposure, the trauma type, and any coping strategies that they had developed prior to or had developed as a result of other trauma events. Lester, Wong, and Hendren (2003). With such complex developmental dynamics present in childhood, the resultant complexity of negative effect potential boggles the mind. Even considering the relatively generalized and often criticized developmental models of cognitive, psychosexual, social, moral, and faith development, the potential for damage in even one of these areas clearly have potential to impact others, if not all areas of development. Even cursory review of the major models by Freud, Piaget, Kohlberg, Erikson, and Fowler will easily demonstrate how each (with the exception of Freud) has to some degree built upon the previous development theory to explain another facet of human development. Placed side by side, most professionals may agree that one of the models, without the others, does not give an accurate or full view of human development. Even when considered this way, one has the intellectual sensation that even these giants in the field have not fully articulated the human development process, subtleties, or complexity. The classic models of human development have only given a basic scaffold to further articulate the subtleties of development. By way of illustration of this complexity, Perry (1996) elaborates, using an example of a PTSD child in school:

Mismatch between modality of teaching and the ‘receptive’ portions of a specific child’s brain occur frequently. This is particularly true when considering the learning experiences of the traumatized child—sitting in a classroom in a persisting state of arousal and anxiety—or dissociated. In either case, essentially unavailable to process efficiently the complex cognitive information being conveyed by the teacher. This principal, of course, extends to other kinds of ‘learning’—social and emotional. The traumatized child frequently has significant impairment in social and emotional functioning. These capabilities develop in response to experience—experiences which these children often lack—or fail at. Indeed, Hypervigilant children frequently develop remarkable non-verbal skills in proportion to their verbal skills (street smarts). Indeed, often they over-read (misinterpret) non-verbal cues—eye contact means threat, a friend touch is interpreted as an antecedent to seduction or rape—accurate in the world they came from but now, hopefully, out of context.

It would appear that just about every childhood developmental area would be profoundly affected in the above example, and demonstrates how the stress disorder readily impacts all spheres of the child’s life, in all environments, and likely, at all times. The child simply cannot escape from the trauma and subsequent trauma effects; their bodies and brains contain all of the trauma-learned ingredients for coping with a world that they essentially perceive as primarily dangerous, unpredictable, and unsatisfying.

School, of course is a highly significant aspect of a child’s developmental process, and it is often at school where the child’s symptoms become noticeable to a person outside of the child’s family of origin. The effects that the front line care-giver (the teacher) sees in the child may not impress as PTSD. As mentioned earlier, diagnosis of stress disorders in children who have been victims of interpersonal violence are frequently either under diagnosed or misdiagnosed. Ever greater evidence is being articulated as to why this is may be so; it appears that Acute Stress and Post Traumatic Stress have distinctly different presentations in children than in adults. At the Center for the Study of Childhood Trauma in Chicago, a study has illustrated several pertinent points for the conversation: the study found that 85% of the children who were diagnosed with PTSD also had a co-morbid DSM diagnosis, and many of the cases had only three clear features of PTSD, including a documented history of traumatic events, escalation of symptoms upon re-exposure to trauma-specific cues, and noted increase in agitation or hyperarousal. (Perry, 1994) Clearly, the co-morbid diagnoses may cloud or overshadow what is perhaps the more fundamental diagnosis (or source of the other, co-morbid diagnoses) of PTSD. Further, the Chicago study also has identified that among the children who have been severely traumatized within the first three years of life, there appears to be what Perry calls a “post traumatic pervasive developmental delay”. (Perry, 1994) Once again, in the front lines of the treatment field, there is often an initial or ‘rule out’ diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder in association with PTSD in children, with these children receiving multiple complaints from school teachers concerning their immaturity and inability to self-regulate in the classroom.

Adding to the problems of gaining accurate diagnosis of stress disorders is the nature of interpersonal violence, the child’s age, and the effects of trauma on memory. In very young children (under age four) and when a child is under severe stress, the encoding of information or traumatic events to memory is impaired, making later accessibility and retrieval spotty at best. (Nader, 2001) Once the child begins to be identified as having behavioral problems and mental health symptoms, usually at the time the child enters pre-school, the child is likely not able to articulate to a care giver the facts of the trauma that produce the effects. In cases where the abuse was either physical or sexual, the adult perpetrator clearly has reason not to suggest that the child’s symptoms are from anything other than the much safer co-morbid diagnosis. The child of course, also has reason to ‘go along’ with this analysis, as they have vested interest in not angering the perpetrator.

Not all abuse, of course, is as obvious as a broken bone or visible bruising. Osofsky (2004) notes that traumas can be exceedingly subtle, and not easily observed by a teacher or counselor; the effects of dysfunctional interaction, irregular availability of the primary care giver, and low quality care may be only salient to the child. (p.70)

On the other hand, a significant portion of the children accurately and timely diagnosed with Acute or Post Traumatic Stress will demonstrate a wider and clear symptom set matching the DSM criteria, including cluster of behaviors surrounding re-experiencing of the trauma (intrusive dreams, and recurrent, unwanted recollections of the critical event) , avoidance, numbing and detachment (including memory difficulties), and physical agitation and distress at times of no danger (sleep disturbance, generalized anxiety and physical agitation). In addition to the DSM symptom clusters, progressive work in identifying other discrete impact areas of PTSD have been defined by Wilson, Friedman, and Lindy (2004), including psychological alterations, relational difficulties, and alterations in ego structure (p. 41). Such ever increasingly refined views of the effects of critical, traumatic interpersonal events imply profound, universal effects for the traumatized child’s growth and development.

This clinician’s anecdotal observations of multiple cases of PTSD in younger children leads to the assertion that such children present as developmentally delayed at least, and demonstrate stark and significant regressions while experiencing intense symptoms of their PTSD. Such demonstrations include an increased clinginess to safe caregivers, indiscriminate approach to strangers, regressions in speech, either affected or genuine helplessness, regressions in toileting, and often-aggressive manipulation of their own feces. Some other behaviors are exceedingly strange, such as regressions into fantasy that emulates psychosis, self harm to genitalia (in sexual abuse cases), and rapid, bi-polar like mood changes. All of which may lead the diagnostician who is not fully informed of the child’s history to come to a conclusion other than PTSD. But careful review and integration of the work of Nader and Perry in diagnostic consideration could relieve misdiagnosis: Nader ( 2001) notes that children with PTSD will exhibit loss of innocence with various signs of precocious development, including premature knowledge and many atypical characteristics for their age. (p284), while Perry (1994) notes that the most consistent symptom finding in cases of childhood PTSD is autonomic nervous system hyperarousal. These basic markers, while not being exclusive of other childhood mental health diagnoses, could be, in the skilled clinician’s repertoire, a useful diagnostic advantage.

Richters and Volkmar (2001) assert that in the area of accurate diagnosis, it is very important that the diagnostician gain both an accurate history from multiple sources and correctly interpret the family context in which the abuse occurred, because both are predictive of child functioning. They also note that there are significant differences in the information gained from the different sources. There could be a variety of reasons for this, including the simple fact of source perspective to the reactivity of observers to the facts of abuse. Accurate assessment of the family context that the abuse took place in points to the logical differences in ultimate child functioning and development of PTSD symptoms between a single incident of violence as opposed to an ongoing pattern of abuse.

Another readily observed hallmark of PTSD in child victims of interpersonal abuse is disturbed relational attachment. Indeed, such disturbances can be seen very early in the child’s life, as is implied in a study on intergenerational transmission of trauma by Schwerdtfeger and Goff (2007), which found that pregnant women who had experienced sexual abuse as children demonstrated a lower quality of attachment to their unborn children. In older children, once interpersonal abuse has occurred with an accompanying PTSD symptom set, there appears to be a logical need for the child to be able to re-establish a close, supportive, and trusting relationship with an adult in order for the child to heal. Since much, if not most childhood interpersonal abuse occurs between the child and biological relative (read parent), the dynamics of this relationship likely inhibit the child from finding such an adult. In fact, even if the child can find such an adult, they still may have difficulty in establishing effective, helpful attachment due to the abuse. (May, 2005)

The nature of child maltreatment being a cross generational issue that may continue to be ‘passed down’ in a family is axiomatic; Fonagy (1999) proposes that relationship violence might be assessed as a dysfunctional response to an individual’s disorganized attachment system in infancy, along with a history of abuse and an absent male parental figure. This then points to the important area of early intervention with children in order to break the intergenerational chain of child maltreatment. In other words, poor attachment leads to more poor attachment.

All of these negative effects of the trauma(s) that a child may endure may at first be assumed to be contained by the constraints of the child’s local, intimate environment, namely the family context in which the trauma may have occurred, and not “seep out” very much from either the context or the child’s stage of development. But this is clearly not so: in an experiment with adults who had been childhood victims, at New York University, Berenson and Andersen (2006) demonstrated how victims of interpersonal abuse can transfer their emotions and behaviors to unrelated others who have not harmed them in any way. Study by Briere and Elliott (2003) on adult ramifications of childhood trauma also suggest a reliable relationship exists between child maltreatment and later adult trauma symptoms. Schore (2002) speaks about “traumatic attachments” that are typified by episodes of hyperarousal and dissociation and how these are “imprinted into the developing limbic and autonomic nervous systems of the early maturing right brain.” This certainly implies that the child’s ability to attach in a healthy manner to others in the future would be greatly impaired.

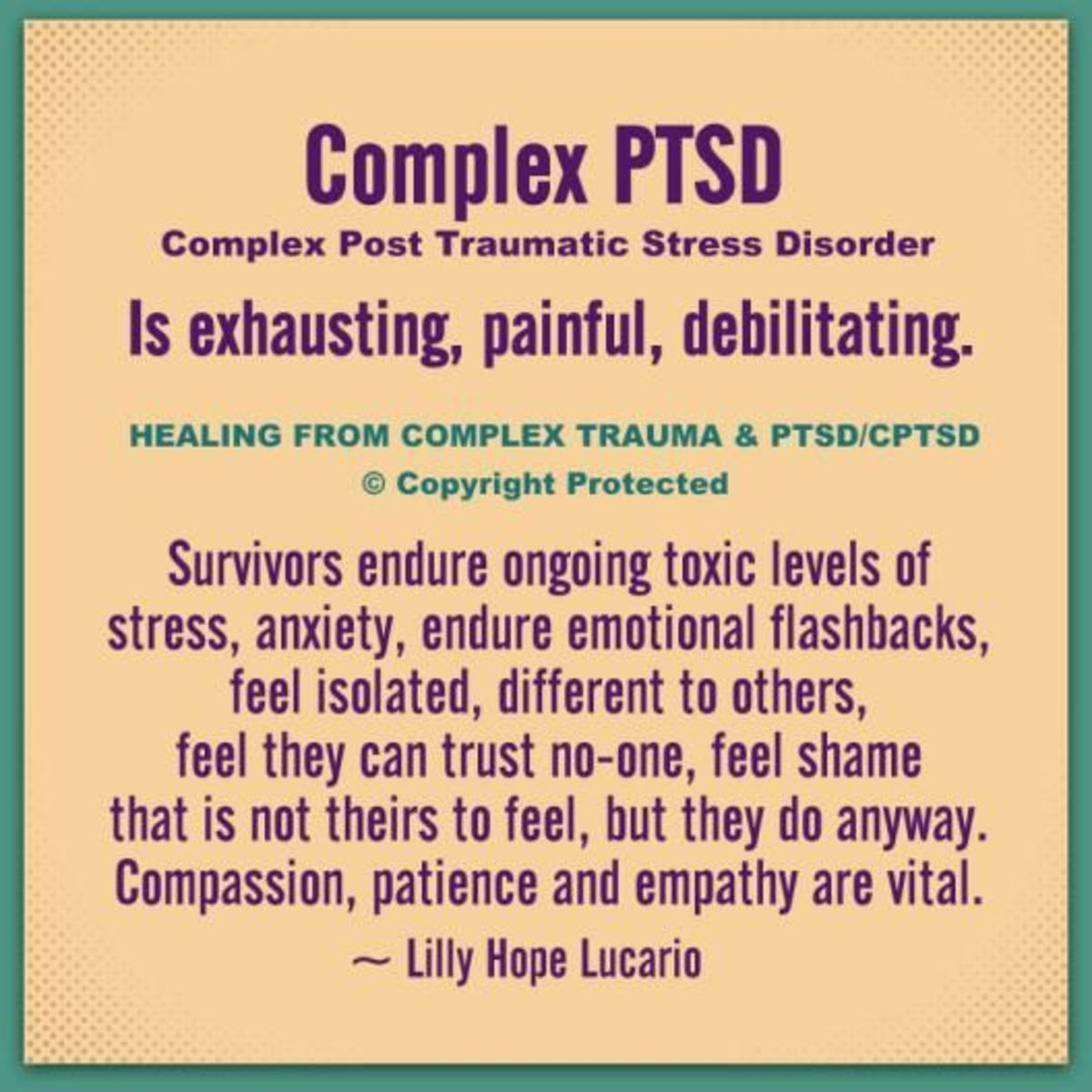

Indeed, early childhood trauma resulting in diagnosable PTSD, left untreated, or inadequately treated, will have life-long effects to various degrees and in various directions. In an analysis of variances demonstrated in a study of sixty six PTSD adults who were victims of abuse, those who had the highest mean scores for PTSD symptoms also displayed fearful and preoccupied attachment styles and negative view of the self. Muller, Sicoli, and Lemieux (2000) Heim, Newport, Bonsall, Miller, and Nemeroff (2001) state:

It is now well established that early adverse experiences constitute a major risk factor for the development of major depressive disorder and certain anxiety disorders, including PTSD. In adulthood, symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as posttraumatic stress symptoms often exacerbate in relationship to acute chronic life stress. We have, thus, hypothesized that stress early in development may alter the set point of the stress response system, rendering these individuals particularly vulnerable to stress and increasing their risk for stress-related diseases.

This theory appears to be quite sound, but verifiable and reliable data demonstrating stronger correlations between early trauma and later adult symptoms would increase the power of the theory from ‘risk factor’ to ‘causation’. One key appears to be in a closer examination of the proposed connection between the observable (child specific) behavioral signs of PTSD in children and the underlying neurobiology that may be affecting the behaviors. Osofsky (2004) identifies a biological phenomenon called “kindling”, which contends that once the biochemical processes involved in PTSD symptom creation occur, repeated episodes of symptom experience act to self-perpetuate the disorder, in a never ending cycle of pre-primed, painful stress episodes. (p.49)

Lester, Wong, and Hendren (2003) identify three areas where neurobiology has a role in PTSD: The maturation and reorganization of brain structures and their function and influence, physiological processes such as neuroendocrine and neurotransmitter influences and fluctuations, and individual personality resilience and vulnerability expressed in cognition, emotional regulation, and the influence of these on behavior. These strong, altered-from-the-norm bio-chemical influences that result from critical events on a developing child’s brain undoubtedly have effects ranging from subtle nuance in relational interactions to dramatic behavioral and cognitive presentations. Beers and DeBellis (2002) had results from an admittedly small sample of children who had PTSD as a result of maltreatment that illustrated how the PTSD children performed significantly lower on measures of abstract reasoning, attention, and executive function.

There have been several meta-analyses regarding the adult difficulties seen as a result of childhood sexual abuse, including significant evidence of negative short and long term effects on development (Paolucci, Genuis, and Violato, 2001) and difficulties in self-esteem. (Jumper, 1995) Though not specifically linking PTSD as a given to child sexual abuse, a meta-analytic review by Neuman, Houskamp, Pollock and Briere (1996) listed the following symptoms in high significance for co-morbidity with childhood sexual abuse: anxiety, anger, depression, re-victimization, self-mutilation, sexual problems, substance abuse, suicidality, impairment of self-concept, interpersonal problems, obsessions and compulsions, dissociation, post traumatic stress responses, and somatization.

In an article titled The Compulsion to Repeat the Trauma, van der Kolk (1989) links adult issues such as addiction with the effect of abuse trauma creating a hyperaroused person who has difficulty in moderating strong emotions, and requiring a much increased stimulus to activate satisfying self comforting. Strong mind and mood altering substances certainly fit this bill. This is of course, no surprise; adult issues of addiction, sexual dysfunction or sexual crime, as well as educational and socio-economic achievement have long been attached to maltreatment in childhood. In a study at Albany State University of New York that included 557 women who had been victims of domestic violence, it was found that the higher level of cumulative abuse over a lifetime, staring with severe childhood abuse, increased the risk for depression and anxiety later in life for the women. (Carlson, McNutt, Choi, 2003)

Fight or flight is a well-known stress response in animals and humans. Neurological structures that are involved with this process include the thalamus, anterior cingulated, amygdale, hippocampus, cerebellum, and cortex. Activation of the system involves the autonomic nervous system, the immune system, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortial axis (HPA) axis, with peripheral release of andrenocorticotropic hormones and cortisol as well as other central nervous system neurochemical systems. (Lester, et. al. 2003) Activation of these structures, and resultant, repeated chemical dumping due to intense trauma experiences appears to disallow the entire system to readily return to a stable homeostatic state. This in turn, creates the variety of available behavioral signs and symptoms common to PTSD. DeBellis (1999) offers further implications that disruptions in catecholaminergic neurotransmitters and steroid hormones, which are known to modulate the developmental processes of neural migration, differentiation and synaptic proliferation may affect the overall brain development in children. If this were so, it would seem to also imply that that a child still in utero could very well experience significant stressors via the mother’s experience of interpersonal abuse that may result in extremely early neurological damage.

Even after birth, Perry (1994) asserts that children’s brains are “at risk for developing permanent vulnerabilities” due to neurochemical changes, and that in this sense, PTSD can be seen as a developmental disorder.

In a study by DeBellis (1999), there was found to be significant indications of urinary-free cortisol (a reflection of HPA axis regulation) in child test subjects with PTSD and a positive correlation between the duration of the PTSD trauma and with PTSD symptoms of intrusive thought, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Thus, a clear connection exists between PTSD signs and symptoms and bio-chemical changes in the body. Startlingly, Perry and Pollard (1997) have been able to demonstrate how severe neglect impacts the brain of a child, citing a case where an otherwise healthy three year old with an average brain size had a significantly smaller brain and an abnormal development of the cortex.

Conclusions

Basic developmental knowledge is not adequate for timely diagnosis of childhood PTSD as a result of interpersonal violence. Neither is it adequate as a basis for clinical treatment. A more detailed and specified understanding of the mechanisms that produce symptoms, and how these symptoms in turn have a synergistic effect with the child’s development are integral to the formation of adequate and effective responses to post-traumatic stress as a developmental impacting disorder. Under diagnosis and misdiagnosis due to the failure of the wider system to convey the needed information, in a practical manner, down to the front line caregiver of children needs particular attention. Once accomplished, this in turn will assist in the early intervention in childhood PTSD , if not maltreatment and abuse of children. It would logically be concluded that earlier intervention would help to mitigate the probability of life-long dysfunction seen in adults who have suffered interpersonal violence as children.

Though neurological and biological research and results are often beyond the study interest and capability of many caregivers, it becomes also incumbent upon the field to interpret and make useable the findings that could help guide treatment and provide groundwork for the development of more effective treatment, both in terms of initial intervention, medication development and counseling-therapy approaches.

Such profound evidences of chemical changes and brain structure alterations in abused children make questions such as “does interpersonal violence and trauma affect a child’s development?” quite moot. It would appear that the research presented on the physical aspects of trauma on a child’s brain imply that there are certain aspects that may not be readily reversible. While reversibility of bio-chemical processes, once altered by trauma may not be a productive avenue of further research or actual treatment, helping victims to find alternative means of coping and establishment of satisfying relational attachments seems to be reasonable.

Indeed, a positive belief in the resiliency of a child, and the relative plasticity of their development gives hope that creation of positive living and experiential environments can significantly alter the outcomes that are typical of PTSD as a result of interpersonal violence in children. All of the research presented seems to point to the fact that PTSD in maltreated children requires a comprehensive treatment approach that makes treatment of their developmental issues integral to the overall success of treatment, rather than a narrow, simplified, behavior shaping approach that typifies most current practices.

Beers, Sue, and DeBellis, Michael. (2002). Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159:483-486, March 2002.

Beiere, J. and Elliott, D. (2003). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27 (2003) 1205-1222.

Briere, J., & Elliott, D.M. (1997). Psychological assessment of interpersonal victimization effects in adults and children. Psychotherapy, Volume 34, Winter 1997, number 4.

Berenson, Kathy. (2006). Childhood physical and emotional abuse by a parent: transference effects in adult personal relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 32, No. 11, 1509-1522. (2006).

Broderick, Patricia & Blewitt, Pamela. (2006). The Lifespan: Human Development for Helping Professionals. Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall, New Jersey. 2006.

Carlson, Bonnie, McNutt, Louise-Anne, & Coi, Deborah. (2003). Child and adult abuse among women in primary health care. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vo. 18, No. 8, 924-941 (2003).

DeBellis, Michael D. (1999). Developmetnal Traumatology: Neurological Development in

Maltreated Children with PTSD. Child Maltreatment , September 1999, Vol. XVI, Issue 9.

Fonagy, Peter (1999). Male Perpetrators of Violence Against Women: An Attachment Theory Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, January, 1999.

Ford, J., Racusin, R., Ellis, C., Daviss, W., Reiser, J., Fleischer, A., & Thomas, J. (2000). Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomology among children with oppositional defiant disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Maltreatment, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2005-217 (2000).

Heim, C., Newport, J., Bonsall, R., Miller, A., & Meneroff, C. (2001). Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivor of child abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158:575-581, April, 2001.

Hishaw-Fuselier, S., Heller, S., Parton, V., Robinson, L., & Boris, N. (2004). Truama and Attachment: the case for Disrupted Attachment Disorder. J.D. Osofsky (Ed.), Young children and trauma: intervention and treatment. (pp. 47-68). New York: The Guilford Press.

Jumper, S.A. (1995). A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to adult psychological adjustment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 19, 715-728.

Lester, Patricia, Wong, Susan, Hendren, Robert. (2003). The Nuerobioligcal Effects of Trauma.

Adolescent Psychiatry, 2003.

May, Joanne. (2005). Family attachment narrative therapy: healing the experience of early childhood maltreatment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, July 2005.

Muller, Robert, Sicoli, Lisa, and Lemieux, Kathryn. (2000). Relationship Between Attachment Style and Post traumatic Stress Symptomology Among Adults Who Report the Experience of Childhood Abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, Vol. 13, No. 2, April, 2000.

Nader, K. (2001). Treatment Methods for childhood trauma. In Wilson, J.P., Friedman, M.J., & Lindy, J.D. (Eds.) Treating psychological trauma & PTSD (pp. 278-334). New York: The Guilford Press.

Neuman, D.A., Houskamp, B.M., Pollock, V.E.,& Briere, J. (1996). The long term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse in women: a meta-analytic review. Child Maltreatment, 1,6-16.

Perry, BD. Neurobioligical sequelae of childhood trauma: post traumatic stress disorders in children. In: Catecholamine Function in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Emerging Concepts

(M. Murburg, Ed.) American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC, 253-276, 1994.

Perry, Bruce. (1996). Violence and Childhood trauma: Understanding and Responding to the Effects of Violence on Young Children. Grund Foundation Publishers, Cleveland, Ohio. 1996, pp. 67-80.

Perry, BD & Pollard, D. Altered brain development following global neglect in early childhood. Society For Neuroscience: Proceedings from Annual Meeting, New Orleans, 1997.

Richeters, Margot Mosher, and Volkmar, Fred R. (1994). Reactive Attachment Disorder of Early Childhood. J.Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 1994, 33, 3: 328-332.

Schore, Allan. (2002). Dysregulation of the right brain: a fundamental mechanism of traumatic attachment and the psychopathogenesis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Australian and New Zealand Jounral of Psychiatry, 36(1):9-30, February 2002.

Schuder, Michelle, and Lyons-Ruth, Karen. (2001). Hidden Trauma in Infancy. In Wilson, J.P., Friedman, M.J., & Lindy, J.D. (Eds.) Treating psychological trauma & PTSD (pp. 69-104). New York: The Guilford Press.

Schwedtfeger, K.L. & Goff, B.S.N. (2007). Intergenrational transmission of trauma: exploring mother-infant prenatal attachment. Journal of Truamatic Stress, 20, 39-51.

Vander Kolk, Bassel. Re-enactment, Revictimization, and Masochism. Psychiatric Clinics of North America , Vol. 12, No. 2, 389-411. June, 1998.

- John Briere

Further pertinent academic research. - The Wounded Healer Journal

Enduring PTSD healing resource. - American Acadmey of Experts in Traumatic Stress

Locate a specialist. - Trauma Pages

Basic information about stress disorders. - Professional Website

Free content on child specific PTSD treatment.